Cases, Human Rights News / Indonesia, West Papua / 13 September 2024

The Indonesian government’s ambitious plan to create a one-million-hectare rice field in the Merauke Regency, Papua Selatan Province, is moving forward without proper consultation with indigenous communities and despite significant environmental risks. On 12 July 2024, the Minister of Environment and Forestry (MoEF), Siti Nurbaya, issued Minister of Environment and Forestry Decree No. 835 of 2024 on Approval of Forest Area Use for Food Security Facilities and Infrastructure Development Activities in the Framework of Defence and Security on behalf of the Indonesian Ministry of Defence covering 13,540 hectares of Protected Forest Area, Permanent Production Forest Area and Convertible Production Forest Area in Merauke Regency.

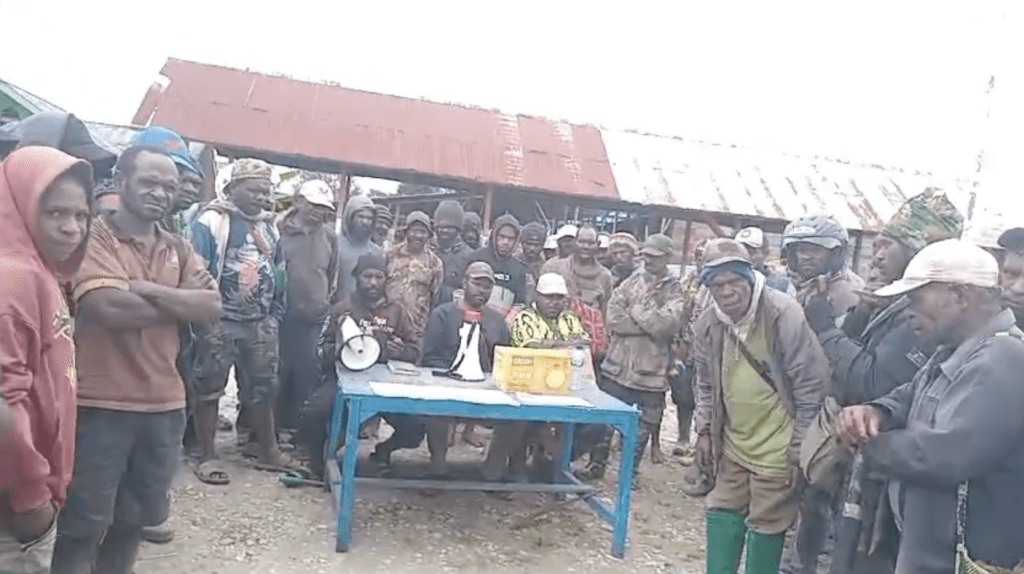

The project, part of the National Strategic Project (PSN), has seen the arrival of hundreds of excavators and heavy equipment, raising alarm among human rights and environmental organisations. According to the information received, the project coordinator, the Indonesian entrepreneur Mr Andi Syamsuddin Arsyad aka. Haji Isam, ordered a total of 2,000 excavators from China to implement the project. HRM received photos and videos showing the arrival of excavators in the project area by ship. One video shows the excavators clearing large areas of land (see videos and photos below, source: independent HRDs).

The project gravely violates the principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), a fundamental right of indigenous peoples. According to press relese published on 13 September 2023 by the Indonesian foundation ‘Pusaka Bentala Rakyat’ (PUSAKA), local indigenous Malind communities, including the Gebze Moywend and Gebze Dinaulik clans, report that their lands, hamlets, and customary forests have been seized without any prior deliberation or consensus. This blatant disregard for indigenous rights is further exacerbated by the presence of armed military personnel securing the project implementation.

The indigenous Malind people, holding the customary land rights in the project area, have firmly rejected all forms of corporate investment on their customary lands. This unified stance was declared by various Malind communities in response to the Indonesian government’s National Strategic Project aiming to establish sugar and bioethanol self-sufficiency and a food barn project spanning millions of hectares in Merauke. Indigenous communities have expressed deep concerns about the potential loss of their lands, forests, and cultural heritage to large-scale development projects.

This rejection highlights the ongoing struggle for indigenous rights and environmental preservation in West Papua. The communities’ concerns stem from past negative experiences with corporate interventions and fears of marginalisation and cultural erosion. The call for intervention from the South Papua People’s Assembly and the Merauke Regional Government emphasizes the need for government accountability and respect for indigenous rights in development planning, urging a re-evaluation of national strategic projects that potentially violate human rights.

Environmental concerns are equally pressing. The project area overlaps with 858 hectares of natural forests and peatlands, as indicated in the Indicative Map of the Termination of Business Licensing (PIPPIB). The large-scale destruction of these ecosystems will significantly increase carbon emissions, directly contradicting Indonesia’s commitments to reduce greenhouse gases. The lack of transparency and the absence of an FPIC-based consultation with indigenous communities support allegations that the project lacks proper environmental impact assessments and approvals. Affected communities and environmental organisations have not been involved in discussions or received information on environmental documents.

The Merauke Food Estate project exemplifies a worrying development trend at the expense of indigenous rights and environmental sustainability. It is crucial for the Indonesian government to reevaluate the project, prioritizing inclusive, just, and sustainable development that respects the rights of indigenous peoples and preserves critical ecosystems. Failure to do so will inevitably undermine global efforts to combat climate change and preserve biodiversity on our planet.